The common advice about venting at work is a simple “Don’t do it” because it looks unprofessional. But there’s a place for venting in the workplace—though at times it may be a minefield.

Venting is defined as the free expression of a strong emotion, according to Oxford Languages. Conflict is part of working together productively, and emotions are part of conflict. Suppressing strong feelings is no more a healthy way to interact as a team than letting biting words fly. Both will inhibit the team and organization from tackling tough questions. So, the challenge is for people to learn how to vent maturely and productively.

While we currently live in a world where certain groups such as women and people of color risk taking a hit to their reputation when they express something passionately at work, we imagine a world where there’s equity in the way people’s emotions are received.

To start to take steps toward that world, we need to understand the concept of motivation.

Learn the three primary motives.

According to Core Strengths research, people are driven by three primary motives:

- Concern for People (Blue)

People who are motivated by the protection, growth, and welfare of others. They have a strong desire to help others who can genuinely benefit.

- Concern for Performance (Red)

People who are motivated by task accomplishment and achieving results. They have a strong desire to set goals, take decisive action, and claim earned rewards.

- Concern for Process (Green)

People who are motivated by meaningful order and thinking things through. They have a strong desire to pursue independent interests, to be practical, and to be fair.

When you take the SDI 2.0 assessment, you’ll get a full portrait of how all three blend in your personality, but even if you haven’t taken the assessment yet, keep reading. After seeing these definitions, you probably recognize yourself primarily in one or a blend of two. Everyone falls at a different place on the spectrum of motives because everyone has a different mix of experiences, cultural background, upbringing, values, and more. So, it’s easy to see why, at any type of organization, your team will be made up of people with different primary motives.

This can cause conflict. Primary motives are all about what matters to us most, and at times, what matters to us will collide with what matters to those around us—especially when we’re under pressure. But the three primary motives can also deliver the framework for managing conflict and venting productively.

Choose your response.

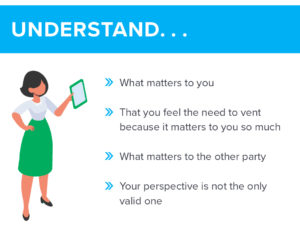

If your primary motive is concern for people, and a colleague is making decisions that, in your opinion, disregard people, it’s natural to get angry and feel the need to vent. This is where you get to choose your response.

The first aspect of choosing the correct response is being able to understand what matters to you (i.e., concern for people). The second aspect is understanding that you feel the need to vent because it matters to you so much.

Then, you can realize that the other party may be acting in a way that’s making you angry because of what matters to them, and that’s equally valid. Walt Whitman, and more recently, Ted Lasso said, “Be curious, not judgmental.” Being curious about your own urge to vent, the context of the situation, and the other person’s values can help you respond productively, venting your emotions with the awareness that your perspective isn’t the only valid one.

Responding with curiosity and honoring what matters most to the other people on the team is essential to developing Relationship Intelligence. But you can respond with Relationship Intelligence and emotion. Saying, “You never care about people” may be unproductive, but saying, “I appreciate and value your focus on results, but I feel concerned that we may not be attending to the impact that driving those results may have on our team” is a potentially more productive and relationally intelligent way of venting.

If the social power dynamics lean in your favor, you can model for others that it’s okay to bring strong emotions to work, but to do so in a way that invites people into a curious conversation as opposed to making them feel judged.

Ted Lasso, the soccer coach on the eponymous hit TV show, is a fantastic example of a person in a position of leadership who leads with both passion and compassion. He vents from time to time, but always makes it clear he respects those around him. He knows intuitively that there’s an advantage in how his venting is perceived, and he creates an equitable environment where his players and colleagues can safely vent, too.

Even as we acknowledge that bias and power dynamics are real, we should aspire to enter into relationships from an equitable place, prioritizing reciprocity and meaningful exchange.

Think of venting as a relational act.

Venting plays an important role in relationships. You’re venting to someone, often about someone. At Core Strengths, we believe the goal of relationships is to build trust, generate commitment, and drive results. And that goes for venting too; the goal of venting should be more than just letting off steam. It should serve a purpose in the relationship.

If you’re going to be effective in the workplace, or anywhere where relationships matter, it’s important to improve the skill of venting productively. The four aspects of high relationship intelligence are positive regard, service orientation, personal accountability, and strength-based agility. When we vent, we should be thoughtful about maintaining those four qualities to increase the likelihood that our venting will serve a productive purpose in the relationship.

People with high relationship intelligence can funnel their anger into a relationally sound moment. That could look like this:

- “Situations like this make me so frustrated, and I know some of the reason is… [motive-based explanation].”

- “I tend to overreact in situations like this, so I might be right now. But I’m feeling as if… [motive-based explanation].”

But we absolutely need to challenge ourselves to vent without getting personal—because that’s no longer venting. That’s verbally abusing.

Find a venting partner.

One strategy is to identify a trusted colleague, friend, coach, or partner you can come to when you have something to vent about. Ideally, this person will also be committed to relationship intelligence and can help you think about the context and reframe it.

The idea of having an outlet for your need to vent is so you don’t go into fight-or-flight mode, either exploding with words you’ll regret later, or shutting down and bottling up your emotions. Ask the venting partner to let you get the raw statement out first, then help you problem-solve, respectfully pushing back on you and challenging your assumptions.

Be careful not to choose someone who will just support your perspective. For a venting partner to add value, they need to be willing to consciously help you develop this skill and navigate the minefield of venting.

The long-term value of venting productively.

We often spend our individual contributor years developing and refining our self-awareness. As we reflect on what matters to us and how our primary motive(s) cause us to take some strengths too far, we can better understand why we frustrate people and also why we get frustrated by others’ behavior.

As you grow in your career and begin to lead bigger projects, this self-awareness will be incredibly helpful. But you’ll need to take it a step further and develop the skill of venting productively. Because situations will come up where you feel the need to vent and you can’t just walk away from the situation.

And of course, as humans, we’ll make mistakes. We may get too heated and vent unproductively without taking the time to choose our response. When this happens, it’s best to apologize from a place of motive, too, and show you’re learning and growing.

Core Strengths has courses and workshops to help you learn how to vent productively and manage team conflict. Learn more about our conflict management solutions here.